Beyond Time Blindness

Understanding ADHD's Recursive Temporal Architecture

Beyond Time Blindness: Understanding ADHD's Recursive Temporal Architecture

How temporal incongruity shapes identity, and why effective intervention requires recognizing different forms of temporal intelligence

Like many clinicians, my initial understanding of ADHD centered on attention difficulties. But years of working with neurodivergent adults revealed something unexpected: their most profound struggles seemed to originate from fundamentally different ways of experiencing time itself. What I've come to understand as temporal incongruity: the persistent mismatch between their internal temporal processing and the linear time expectations of the external world.

The recursive processing phenomenon becomes clear when examining how individuals approach seemingly routine tasks like client email responses. Rather than linear task completion, the mind engages in simultaneous multi-temporal analysis, connecting the response to past client feedback, projecting multiple versions of potential reactions, linking communication choices to professional identity, and attempting to solve for every possible future misunderstanding. What the linear world registers as procrastination or delay actually represents deeply complex, recursive engagement across multiple temporal dimensions. This is temporal incongruity in action.

This mismatch creates an internal tension that goes far beyond time management difficulties. The harder individuals try to conform to neurotypical temporal expectations, the more alienated they become from their own neurological reality, leading to a gradual erosion of selfhood that manifests as shame, perfectionism, and chronic feelings of inadequacy.

Understanding this temporal incongruity reveals something fundamental that conventional ADHD approaches have missed entirely. What we've labeled as attention deficits may actually represent expressions of a fundamentally different temporal architecture, one that operates through cognitive principles we're only beginning to recognize.

From Time Blindness to Recursive Temporality

The term "time blindness" has gained considerable popularity in recent years, but I believe it fundamentally mischaracterizes the ADHD temporal experience. When I first encountered Dr. William Dodson's concept of "curvilinear time" (Dodson, 2020), I became intrigued not by its geometric definition, but by how it suggested something far more sophisticated than simple temporal impairment.

This insight led me to reconceptualize ADHD temporal processing as recursive rather than deficient. Understanding temporal incongruity requires recognizing that ADHD minds don't just process time differently. They operate through fundamentally different cognitive architecture that loops back on itself while still moving forward.

Recursive thinking moves like cursive writing: flowing forward through loops and curves that connect ideas meaningfully, where each apparent return backward actually enables the next forward movement. Just as the loop in a cursive 'e' seems to retreat but actually creates the essential connection point for the next letter, recursive thought patterns circle back through previous experiences not as stuck repetition, but as cognitive linking that enables more integrated understanding to emerge.

The clinical significance of this distinction becomes clear when we contrast recursion with rumination. Unlike simple rumination, which represents being stuck spinning around a single point, recursive thinking keeps moving forward even if that movement includes returns and detours. Rumination is like repeatedly tracing the same letter in the exact same spot, creating mental movement without forward progress. Recursive thinking, however, flows like skilled calligraphy where each loop serves the larger purpose of creating meaningful connections between ideas, building depth through connection rather than mere repetition.

The Phenomenology of Recursive Time

When ADHD consciousness operates through this recursive temporal architecture, it creates lived experiences that differ fundamentally from neurotypical time perception. Past experiences don't remain safely archived in memory; they loop back into present awareness with startling emotional immediacy. Future consequences may feel utterly remote or suddenly overwhelming when they collapse into the immediate moment. For many ADHD individuals, only two temporal states feel genuinely real: "now" and "not now" (Barkley, 2012).

Consider how this recursive temporality affects something as routine as choosing what to eat for lunch. The neurotypical mind weighs current hunger against available options in a relatively straightforward decision process. But the recursive mind simultaneously processes how this choice connects to past dietary decisions, projects potential energy and mood effects, considers social implications if eating with others, and evaluates how this fits with longer-term health goals. Past, present, and future collapse into a single, temporally saturated decision point where cursive-like thinking attempts to connect multiple time domains at once.

From the outside, this appears as indecision or overthinking. From the inside, it represents sophisticated systems analysis that accounts for variables and interconnections across multiple temporal dimensions. This is the cognitive equivalent of creating meaningful letter connections in cursive writing where each stroke serves both immediate and long-term compositional purposes.

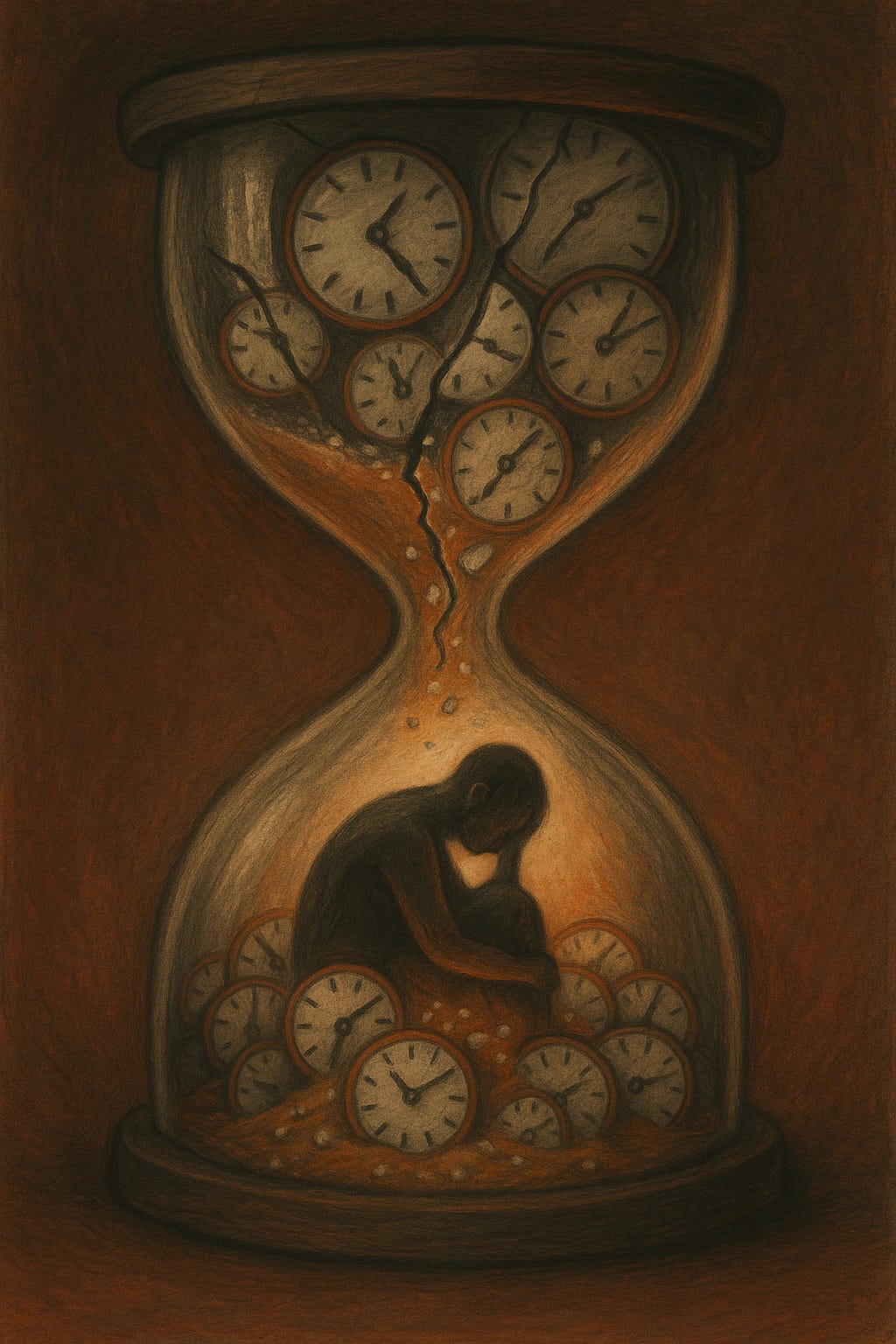

The Sandcastle Self: When Architecture Requires Daily Reconstruction

This recursive temporal processing creates practical challenges that extend far beyond apparent indecisiveness. Unlike neurotypical brains that maintain relatively stable organizational and motivational structures across days, ADHD minds must consciously reconstruct these systems each morning in what I call the "sandcastle phenomenon."

Each day begins like building a sandcastle from scratch: constructing the necessary infrastructure for focused attention, emotional regulation, and goal-directed behavior. Just as cursive writing requires reestablishing proper pen grip and letter flow each time you begin writing, recursive minds must rebuild their cognitive coordination systems daily. The cognitive architecture that supports complex thinking doesn't persist automatically. It requires deliberate reconstruction.

Each evening, sleep washes away much of what has been painstakingly built, requiring fresh construction the next day. The exhaustion ADHD individuals describe isn't laziness. It's the genuine fatigue of people who must rebuild their operational selfhood daily while simultaneously meeting demands from a world that assumes stable, continuous temporal experience.

This sandcastle metaphor illuminates why conventional time management advice fails so spectacularly for recursive minds. When your sense of temporal continuity must be consciously reconstructed each day, productivity strategies designed for linear time processing feel like instructions written in a foreign language, not because of lack of intelligence or effort, but because they assume a neurological foundation that simply doesn't exist.

When Temporal Differences Become Identity Wounds

The implications of this daily reconstruction extend far beyond practical organization challenges to affect fundamental identity formation. When the basic infrastructure of cognitive functioning must be consciously rebuilt each day, any disruption to that process begins to feel like a threat to one's competence as a functioning adult.

Time management, organizational skills, and structured routines occupy a particular cultural position. They're viewed not just as practical abilities but as essential markers of independent adulthood. When these seemingly basic aspects of "adulting" represent core daily reconstruction challenges, feelings of inadequacy and shame become almost inevitable.

What makes ADHD-related shame particularly destructive is its recursive nature, operating through the same cognitive patterns that create the original temporal challenges. Each missed deadline doesn't merely create practical consequences; it reactivates the emotional residue of every previous temporal failure, creating shame spirals that extend backward through memory while simultaneously projecting forward into imagined future disappointments. Like interrupted cursive writing that loses its natural flow and must be restarted, each temporal failure disrupts the recursive mind's sense of cognitive continuity, making the present moment saturated with shame from multiple time periods simultaneously.

Many individuals develop perfectionism as a compensation strategy, believing that if they could just execute flawlessly, these neurological differences could be overcome through sheer force of will. When daily life feels unpredictable and time seems to slip away without warning, the fantasy of perfect control becomes psychologically appealing.

Yet perfectionism creates what I term the peak performance trap. ADHD brains operate with inherent variability. Attention, motivation, energy, and temporal awareness naturally fluctuate based on countless internal and external factors. Demanding consistent performance from recursive thinking is like requiring someone to write cursive at identical speed and quality regardless of whether they're tired, stressed, or working with poor materials. Setting expectations based on optimal days creates conditions where shame inevitably follows when natural neurological variation occurs, reinforcing rather than resolving the original temporal struggles.

The Neuroscience of Temporal Coordination

Understanding why perfectionism becomes such a counterproductive response requires examining what recent neuroscience reveals about temporal processing in ADHD brains. The perfectionism trap reflects more than psychological dynamics. It represents a fundamental mismatch between how these brains naturally coordinate temporal information and what conventional productivity approaches demand.

Research focuses on what scientists call "temporal foresight": the brain's capacity to make future events feel emotionally real and motivating in the present moment (Barkley, 2012). This neurological process operates fundamentally differently in ADHD minds, creating what the literature terms temporal myopia: future consequences exist intellectually but lack the emotional salience necessary to guide present behavior.

This neurological difference mirrors exactly what we observe in cursive writing development. Just as children learning cursive must coordinate planning several letters ahead while executing current strokes, ADHD brains appear to be managing temporal coordination across multiple time scales simultaneously. This represents a more complex task than the linear, step-by-step temporal processing that conventional interventions assume.

The disconnect occurs not at the level of intellectual understanding. ADHD individuals often demonstrate sophisticated analytical capabilities when examining temporal relationships intellectually. Rather, the difference lies in embodied emotional experience. Future events simply don't generate the visceral sense of urgency that they do for neurotypical brains until they become immediately present, much like how cursive writers must feel the flow between letters rather than just knowing intellectually how letters should connect (Sonuga-Barke, 2005).

Reframing Recursion as Temporal Intelligence

Once we understand temporal foresight as sophisticated temporal coordination rather than simple deficit, the entire foundation for understanding recursive processing must shift. Breaking free from the shame and perfectionism cycle requires more than reducing unrealistic expectations. It demands recognizing that what we've labeled as cognitive deficits may actually represent sophisticated temporal intelligence operating through different principles than linear thinking.

The ADHD client who spends hours crafting an email response exemplifies this temporal intelligence in action. Rather than seeing this as procrastination or perfectionism, we can recognize sophisticated systems thinking that considers how this response flows from past communication, connects to relationship dynamics, influences future interactions, and integrates with personal and professional identity concerns. This represents cognitive sophistication that accounts for temporal and relational variables that linear approaches might miss entirely. This is the intellectual equivalent of creating meaningful letter connections in cursive writing where each stroke serves both immediate and long-term compositional purposes.

This recursive depth can become problematic when it occurs without adequate external structure or when time pressure creates anxiety that interferes with natural completion of analytical cycles. But the underlying cognitive process represents a form of temporal intelligence that deserves recognition and skillful support rather than elimination.

Clinical Implications: From Assimilation to Accommodation

Recognizing recursive processing as temporal intelligence means that effective intervention cannot focus on making ADHD brains operate more like neurotypical ones. Instead, we need approaches that honor this different temporal architecture while providing environmental support that allows it to function optimally.

This understanding leads to distinguishing between temporal assimilation and temporal accommodation. Temporal assimilation attempts to train ADHD minds to process time linearly, while temporal accommodation creates environmental conditions that support recursive temporal processing.

The difference becomes clear through practical application. Temporal assimilation might involve teaching time management techniques designed for linear thinkers: breaking tasks into rigid sequential steps, using inflexible scheduling systems, or practicing faster decision-making. Temporal accommodation, by contrast, provides visual temporal scaffolding that makes abstract future events more concrete, creates transition rituals that help close recursive loops, or establishes collaborative structures that externalize complex analytical processes.

Like providing high-quality paper and proper lighting for cursive writing, temporal accommodation supports natural cognitive patterns rather than forcing conformity to different cognitive styles. The goal isn't to eliminate recursive processing but to create conditions where it can unfold productively rather than becoming trapped in overwhelming spirals.

Supporting Authentic Temporal Being

This temporal understanding provides what I call existential validation: helping individuals recognize that their struggles with conventional time structures reflect neurological differences rather than personal failures. When clients begin to understand their recursive temporal processing as cognitive depth rather than deficit, accumulated shame around temporal struggles can begin to dissolve.

The therapeutic work resembles skilled calligraphy instruction rather than typing lessons. Instead of eliminating the loops and flourishes that make cursive both beautiful and functional, therapy focuses on understanding the natural rhythm of recursive connecting movements and providing appropriate tools: optimal environmental conditions, adequate processing time, collaborative structures that allow this cognitive style to produce its most elegant and effective results.

Validation doesn't eliminate the practical challenges of living in a linear-time-structured world, but it transforms the relationship to those challenges. Instead of fighting against their natural temporal architecture, individuals can begin working with it, developing personalized approaches that honor their recursive processing while meeting external demands.

Toward Recognition of Temporal Diversity

When we begin to understand ADHD through this temporal lens, we discover something profound about human cognitive diversity itself. The very aspects of ADHD that create the most shame in our productivity-focused culture (the recursive processing, the complex analysis of possibilities, the deep engagement with meaning and consequence) may actually represent forms of temporal wisdom that our linear-thinking world desperately needs.

The question isn't how to make ADHD brains function more like neurotypical ones. The question is how to create environmental structures that honor the unique temporal intelligence that recursive processing provides while supporting individuals in developing authentic relationships with their own temporal experience.

Rather than offering another productivity system, this understanding suggests a fundamental reorientation toward temporal experience itself. For those recognizing their own recursive processing patterns, the path forward involves shifting from self-criticism toward accommodation. Instead of demanding that organizational systems stand permanently, the question becomes: What is one thing that could make tomorrow's inevitable rebuilding process more sustainable?

For clinicians, understanding recursive temporal processing transforms therapeutic conversations. When clients describe feeling "stuck" or "overwhelmed" by decisions, exploring what different temporal connections they're processing ("What different points in time are you connecting to right now?") can reveal sophisticated cognitive work rather than simple avoidance, opening collaborative pathways for supporting rather than correcting these natural patterns.

The temporal incongruity that underlies so much distress in ADHD may represent more than just one neurodevelopmental difference among many. Understanding recursive temporal processing as the core mechanism driving what we've labeled as attention deficits suggests a fundamental paradigm shift in how we conceptualize neurodivergent cognition itself. Rather than viewing ADHD through the lens of attention regulation failures, this temporal architecture framework reveals sophisticated cognitive coordination operating through different principles than linear information processing.

This temporal processing lens may extend beyond ADHD to illuminate other forms of neurodivergence as well. The recursive patterns, daily reconstruction challenges, and temporal coordination differences we observe in ADHD might represent variations on common themes across the neurodivergent spectrum. If temporal processing constitutes a foundational cognitive architecture that varies among individuals, then many of the symptoms we attribute to attention, executive function, or social communication differences might actually reflect different temporal intelligence patterns seeking environments that support rather than constrain their natural cognitive rhythms.

References

Barkley, R. A. (2012). Executive functions: What they are, how they work, and why they evolved. Guilford Press.

Brown, T. E. (2013). A new understanding of ADHD in children and adults: Executive function impairments. Routledge.

Dodson, W. (2020). What is time blindness? ADDitude Magazine.

Faraone, S. V., & Biederman, J. (1998). Neurobiology of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 44(10), 951-958.

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S. (2005). Causal models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: From common simple deficits to multiple developmental pathways. Biological Psychiatry, 57(11), 1231-1238.

Toplak, M. E., Dockstader, C., & Tannock, R. (2006). Temporal information processing in ADHD: Findings to date and new methods. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 151(1), 15-29.

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-difference metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1271-1288.

For clinicians interested in developing temporal accommodation approaches in practice, I welcome dialogue about how these frameworks might be integrated into therapeutic work. For individuals who recognize themselves in this description, I hope this perspective offers both validation and a foundation for developing more authentic relationships with your own temporal experience.

Wow, Mr Waller-De La Rosa! This hits home on so many levels. Your examples are spot on: choosing an outfit, responding to emails at work, choosing a meal. I absolutely have a complex decision-web going on over all those things; no, it is not a simple decision, not in my brain! There is not one word written that didn't make sense. At 62, I just began to consider maybe I'm ADHD because it is worse in retirement with NO structure. Imagine that. Not good. I look forward to learning more from your perspective. Thank you.